Bishop Tony Clavier: A Son's Portrait

The Triumphs, Tragedies and Winsome Faith of an Episcopal Storyteller.

There are people whose lives contain such texture and contradiction that they defy neat summary. My father’s was one of them. His story doesn’t lend itself to the tidy narratives we often attach to public figures, nor does it fit the clean moral arcs we impose on the people we love. And while it contained many unhappy elements, it touched far too many lives ever to be called tragic. Instead, his life was a slow-burning mixture of brilliance, faith, failure, redemption, and grace.

He was born in 1940 in Worsbrough Dale, South Yorkshire, a child of the coalfields and postwar austerity. His mother, a coal miner's daughter turned district nurse and midwife, divorced when he was five, and so raised him alone in a time when divorce could carry serious social cost. Their relationship was affectionate but often fraught—two strong wills locked in close quarters, trying to make a life together in mid-century England. She was fiercely proud, sharp-tongued, and determined. He was clever and charismatic, with a mind very much his own.

Dad’s childhood spanned three very different worlds: the itinerant life with his mother; holidays with his working-class Yorkshire family in Barnsley; and time spent with the Claviers, a mixed-race West Indian family in London whose cosmopolitan spirit gave him a glimpse of a wider, more diverse world. He carried a complicated pride in all of it. He admired his Clavier heritage tremendously but always thought of himself as a Yorkshireman and Worsbrough Dale as home.

Though he often joked about his schooldays, they were, in fact, pretty brutal for him. He attended a public school in Norfolk where he was bullied and abused—a trauma he rarely spoke of, but which left lifelong scars. He compensated with wit and mischief, masking the sadness he never knew how to name. Throughout his life, he was charming and entertaining, full of stories and vision. He radiated charisma. But very few people ever knew the man underneath. He was strangely both immensely gregarious and intensely private.

The church became his sanctuary from an early age. It gave him a structure, an anchor, and a refuge. At four, he asked his mother to dress his teddy bear (which we still have) as a bishop. He learned the organ, read the Book of Common Prayer alongside adventure novels, and developed an unshakable sense that God had placed something in him that must be lived out.

His path to ordained ministry was neither simple nor straightforward. He drifted through short teaching stints, social work with Shelter, and early ministry. But then, surprisingly, he moved to the United States in 1969, where less than a year later he became a bishop in the newly formed American Episcopal Church (AEC).

He was 30 years old.

For a while, he was brilliant at it. The AEC was tiny, disorganised, and fragile—but under his leadership, it grew into a more coherent and mission-focused church. He avoided the shrill partisanship of many breakaway Anglican jurisdictions. Instead, he offered something gentler: traditional worship, broad Anglican identity, and a commitment to prevent the church from turning into a battleground. During this time, his reaching out to the Episcopal Church resulted in several years of good, though ultimately fruitless, ecumenical talks.

In 1970, he married my mother, Ginger, a young schoolteacher from Charleston, South Carolina. I was born later that year. My younger brother arrived in 1976, just after my Dad had stepped down as Primus to pursue further theological training at Nashotah House. By then, the AEC seemed doomed to failure and my parents’ finances had become precarious. But when the Episcopal Church voted to ordain women, he returned to the AEC and served for the next decade in Florida.

The 1980s were the pinnacle of his ministry. Reappointed as Primus in 1981, he led the AEC into a period of stability and growth. He was also rector of St Peter’s in Deerfield Beach, a church that grew under his leadership from 30 to nearly 300 members, built a new sanctuary, and became a hub of youth ministry and priestly vocations. It’s where my own Anglican faith was nurtured. These were his happiest years—a time when his gifts were fully engaged and his drive and sense of purpose were matched by opportunities.

In 1987, we moved to Charlottesville, Virginia, where he built up another congregation and oversaw the construction of another church. He seemed tireless and irrepressible. But the toll was beginning to show.

The end of his active episcopal ministry began 1991, when the AEC merged with part of the Anglican Catholic Church to form the Anglican Church in America. Dad agreed to step down as Primus to help secure the merger but continued as bishop of the Diocese of the Eastern United States. Sadly, the new leadership dynamic quickly proved difficult. Though officially junior to the new archbishop, he led by far the strongest diocese and remained widely admired. Tensions between them and their respective supporters rose.

Around this time, something in him began to break. After I left for university, I noticed that he was growing more irritable, more withdrawn. He returned to St Peter’s in 1992, but it was no longer what it had been, and neither was he. An affair, followed by damaging public allegations, shattered what remained of his ministry. Though the claims, which were reported second-hand, were never substantiated and he was later cleared, the damage was done. The archbishop offered no support. Dad broke and vanished for weeks.

When he reappeared, he was living with Pat, whom he later married. She gave him stability and care in a season marked by regret and disillusionment. The man whom I met a couple of months later was different. He looked older, broken, and the spark I’d always known in him was gone. He spent his days sculpting clay cartoon figures (I still have his Hooker, Laud, and Taylor) and teaching here and there, living in the shadows of what had been. He sobbed at my ordination. I’ll never forget it.

Then came something like redemption. In 1999, the Bishop of Arkansas received him as a priest into the Episcopal Church. He served first in Pine Bluff, then moved to France to work in the Convocation of Episcopal Churches in Europe. Between 1999 and 2005, glimpses of the man I’d once known returned—his wit, his vitality, his self-confidence.

He softened, too. He came to support women’s ordination and loved to mentor ordinands and young clergy across the theological spectrum. He became a bridge-builder between conservative and progressive Anglicans and wrote regularly for The Living Church blog and later edited The Anglican Digest. The old spark may still have been dimmer, but there was something more open-hearted and vulnerable about him.

A rare form of cancer brought him back to the U.S. in 2005. After nearly dying from pleurisy in 2006, he regained strength and served in South Dakota and then Indiana. He developed a deep friendship with Bishop Edward Salmon and became strongly connected with Nashotah House. But a serious fall with multiple broken bones and a return of the cancer curtailed his work.

Since Dad had little money to retire on, the then Bishop of Springfield offered him two tiny parishes, which he served for well over a decade—his longest appointment anywhere. By then again divorced, he lived alone with a menagerie of pets, including a parrot infamous for telling people to bugger off. Walking had by then become difficult, but he continued to offer what he could. His motto (borrowed from Churchill) was KBO: Keep Buggering On. I think he made some of his best friendships during this time.

In 2016, Presiding Bishop Michael Curry gave him the honorary title of "ecumenical bishop," allowing him to robe and style himself as a bishop without exercising episcopal ministry. It was an unnecessary but generous act of grace, and it moved my father deeply.

Covid began to undo what health he had left. Isolated and inactive, his physical health declined substantially over those two years. So, in 2022 at the age of 82, he finally retired and returned to Britain, settling in sheltered housing near me in Brecon. After 53 years in the U.S.—without ever becoming a citizen—he had come home. His final liturgical act was preaching at my licensing at St Mary’s, Brecon. That sermon was his last word as a bishop, and it was perfect.

My father was a man of deep faith, but in the quiet, unshowy way of his generation. He didn’t perform piety. He lived it in a very Anglican way—in the daily offices, the Eucharist, his deep love of being at the altar. He was a high churchman of the old school: a Prayer Book Catholic who delighted in both the absurdities and glory of classical Anglicanism.

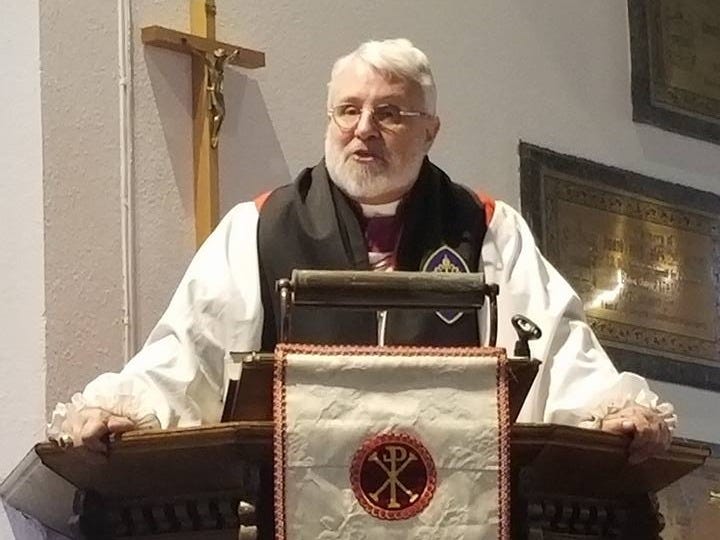

Although he was a supremely impressive bishop at his height, nothing in his ministry was more admired than his preaching. He spoke movingly without notes, with clarity and conviction. He could hold a congregation spellbound. And he had the rare gift of making even complex theology human and relatable. In this way, he was very much like his hero C.S. Lewis. Like him, he was a storyteller at heart.

Dad was largely self-taught with an imposing intellect and a photographic memory, devouring books at astonishing speed. His knowledge of Anglican worthies from across the globe was encyclopaedic. He knew every entertaining anecdote about eccentric clergy so thoroughly—and retold them so vividly—that I began to suspect him as their uncredited source. Besides Lewis, his theological heroes were the Caroline Divines, George Herbert, Michael Ramsey, Eric Mascall, Henry McAdoo, and the Methodist theologian P.T. Forsyth. But his true theological imagination was rooted in the world of make-believe: Rat and Badger from The Wind in the Willows, and Aslan from The Chronicles of Narnia (he also loved Winnie-the-Pooh). To truly understand my father, you needed to know and love those stories. A country parish near Toad Hall would have suited him perfectly.

He was, in many ways, a man out of time—somewhere between (in British terms) an old Liberal and a One Nation Tory, and a royalist through and through. He would have been a magnificent Edwardian bishop of a rural diocese. He idolised Nelson, Wellington, and Churchill almost as much as he disliked jeans, sitcoms, and popular music—all of which he found undignified. He never played games, never watched or played sport, and never understood why other people did. But his conservatism was also consistent: he opposed abortion, the death penalty, and guns, and he had no patience at all for even casual racism—he would call it out with a sharpness that startled.

He remained throughout his life fiercely British—and, for what it’s worth, he identified himself as British rather than English. Every year, he celebrated “getting rid” of the Colonies on the 4th of July and of the Puritans on Thanksgiving. He retained a pride in Empire long after it had become unfashionable to do so, yet always seemed to identify more with the colonised than with the colonisers—perhaps due to our family’s mixed racial heritage. He took me to watch all three hours of Gandhi when I was only eleven. Still, I was well into my adulthood before I could admit that anything American might be superior to anything British.

As a child, I lived in awe of him. He was a deeply affectionate father. A smile, a kiss, the playful raising of his eyebrows, a word of praise, could speak volumes. I never doubted his love.

He had his flaws. He could be rigid, judgemental, and emotionally closed-off about himself. He didn’t suffer fools lightly, and he was too prone to offering mortifying stage-whispered commentary. He utterly lacked the ability to feign interest in things he disliked, and he allowed this to affect his relationship with my brother more than he should. He had a deep need for admiration and an infuriating habit of letting others do things for him. He was hopeless with anything practical, except cooking.

My father’s life taught me that greatness and tragedy often walk hand in hand. He had the gifts to be a figure of lasting influence: charisma, intellect, vision. But poor decisions at crucial moments, combined with ill health and a restless spirit, undermined those gifts too often.

And yet, I can’t think of him without enormous gratitude. He baptised and buried, preached and prayed, far longer than most clergy these days. He showed me what it means to persevere when the world seems against you and you are your own worst enemy. He modelled a faith that was steady rather than showy and rooted in the ordinary graces of bread, wine, and prayer. And he provided me with a winsome model of masculinity rooted in kindness, affection, faith, and the gentler ways of life rather than in machismo, status, or wealth.

More than that, he was always a good father to me. He and I always had very different personalities—I take more after my mother—but he imbued me with many of his loves, and he enjoyed nothing more than sharing them with me. Listening to his sermons week after week influenced my faith as much as his storytelling shaped my imagination. During the last thirty years, my relationship with him followed its own arc—from awe to disappointment, from exasperation to resignation, and finally to something like open-eyed love. Throughout that time, his love and admiration of me never wavered.

When I picture him now, I see him preaching in his prime, that familiar twinkle in his eye when he was in full flow. I see him in his armchair, surrounded by tottering piles of books, a dog at his side. I see him walking with his pronounced waddle, a tweed hat on his head and a walking stick in hand, entertaining his companions with stories. I see him delighting in reading The Wind in the Willows to a classroom of enthralled children.

No life has taught me more. None has asked more of my forgiveness or inspired more of my admiration. My father’s life was extraordinary, painful, luminous, and human. I will be turning it over in my mind for the rest of my own.

Beautiful words capturing such complexity. Well done.

Lovely read Mark. Diolch yn fawr.