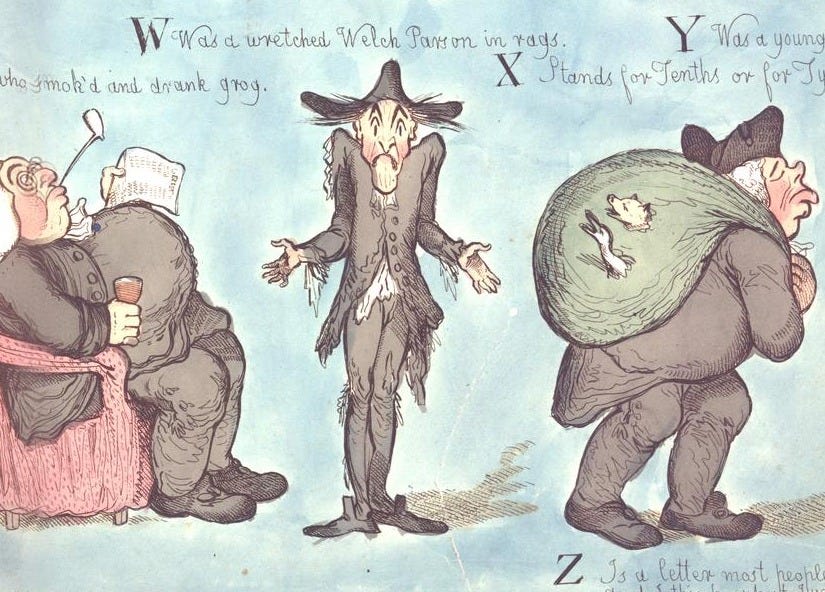

On the wall of my study hangs a copy of Richard Newton’s “A Clerical Alphabet”, a print from 1795. It’s a gloriously irreverent piece of satire — a series of cartoons, A to Z, lampooning the clergy of the day: bishops, archdeacons, canons, even a fiery Methodist preacher. Beneath each figure runs a mocking couplet, gleefully pointing out their flaws. “R was a Rector at prayers went to sleep; S was a Shepherd who fleec’d all his sheep.”

But my favourite is the “W”: a thin, dishevelled parson, with shrugging shoulders and arms outstretched in comic resignation, the caption reading, “W was a wretched Welsh Parson in rags.”

In many corners of Wales, the image of the poor, ragged parish vicar was not just a cruel caricature. It had some basis in fact. If the Church of England in the Home Counties often enjoyed the patronage of landed wealth, producing grand churches with soaring towers and gilded interiors, the Church in Wales — particularly rural Wales — often eked out a humbler existence. Wales, even before the Reformation, was comparatively poor — the medieval Welsh economy was a mere tenth of England’s. The grand Perpendicular churches of north-east Wales — Mold, Gresford, Wrexham — are the exception, not the rule.

The Reformation didn’t enrich the Welsh Church either. My wife’s research into 17th-century clerical wills paints a poignant, often heart-breaking picture: vicars who were literate but desperately poor, leaving behind only a few possessions — a bed, perhaps a Bible, maybe a handful of other books, and a few coins. One can imagine their descendants, a century later, tending draughty, ancient churches with crumbling walls and leaking roofs, trying to carry on in threadbare clericals not far removed from Newton’s cartoonish vision. Theirs was a world almost entirely removed from that of Mr Collins in Pride and Prejudice or Mr Septimus Harding of The Warden.

It’s tempting to view all this simply as a sorry picture of ecclesiastical failure. Yet, living among these churches today, I find myself believing something rather different. There is, I think, a stubborn and “ragged” glory in the shape that Anglicanism has taken in Wales — something uniquely beautiful and altogether good.

Churches Rooted in the Land

You can see it, first of all, in the architecture. Drive through the Welsh countryside, and within a day (if you’re ambitious and disregard speed limits) you might visit upwards of a 100 churches, many dating back to the Middle Ages. Most share a recognizable vernacular style: small, single-aisled, low-ceilinged, built solidly of local stone, furnished with dark oak pews and simple pulpits. The windows are small, filtering the light softly, giving the interiors a sense of deep, enfolding peace.

These churches don’t dominate their landscapes as English parish churches often do. They belong to them. They crouch among the fields and woods, battered by centuries of rain and winds, worn but enduring. In some cases, such as the little church at Cilmery, where the last independent Prince of Wales was killed in 1282, you won’t even find a road leading to them — only a footpath across an often sodden farmer’s field.

Some, however, contain real gems, like the marvellous Llanelieu church, in which you’ll find a precious survival of medieval craftsmanship: a carved and gloriously painted rood screen, speaking of a time when sacred spaces were lovingly delineated from the ordinary world. Another such screen survives at Llananno, still standing proud in a church now silent, a reminder that faith and art once flourished even in the loneliest corners. Thanks to the tireless work of groups like the Friends of Friendless Churches, these treasures have been preserved even when the congregations have dwindled away.

Unlike the grand churches of England, which were often augmented and improved through the centuries by the largesse of wealthy patrons, many Welsh churches remained frozen in time. They were too poor to change much — and that very poverty has, paradoxically, preserved their character.

When Victorian restorers turned their attentions to the churches of England, they often left behind what were effectively new buildings — medieval churches rebuilt according to Victorian fantasies of the Middle Ages. In Wales, the story was usually different. Funds were scarce, and restorations were usually minimal, even perfunctory. Many churches were patched up rather than transformed, and so enjoy a kind of spartan authenticity. Battered by centuries, sometimes stripped of their most elaborate fittings, they yet retain a sense of ancient, lived-in holiness.

And the landscape tells its own story. In places like Defynnog, where an ancient yew tree stands in the churchyard — old enough to have witnessed pre-Christian rites — one senses that these aren’t simply Christian sites, but ancient holy places layered with centuries of reverence older than even the earliest memory. At Patricio, pause to honour St Issui in his quiet shrine, and drop a coin into a holy well that’s likely swallowed offerings since before Rome cast its shadow here.

Eamon Duffy famously described medieval English Christianity as “a religion of the senses” — ablaze with sights, smells, and sounds. Welsh Anglicanism, by contrast, often feels like a religion of place: a faith anchored in stone, rain, and silence. In this sense, its churches and shrines have more in common with ancient standing stones and megalithic sites than with the grand Wool Churches of their own era.

The Persistence of a Minority

Another key part of the story is cultural. By the 19th century, the Church of England in Wales had become a minority faith. Nonconformity — Methodists, Baptists, Congregationalists — swept through Wales like a revivalist wildfire, driven by a democratic, emotionally charged Christianity that often stood in opposition to the formalism of Anglicanism. There was little that Newton’s ragged parson could do to prevent this, entirely unsuited as he was to the Industrial age.

The Church of England, in many parts of Wales, was viewed with suspicion, associated with English rule, social hierarchy, and Toryism. To survive, it had to adapt. It had to become less about pomp and position (however much it didn’t want to) and more about pastoral faithfulness. No doubt, their clergy often failed in this regard. But I’d challenge you to find anywhere more evocative of the deep religious heritage of Wales than the churches in which they served. You can’t stand alone in one and still feel like you’re still entirely in the 21st century – the centuries envelop you like mist, heavy with the breath of a thousand prayers.

The overwhelming rural character of Welsh Anglicanism often feels quieter, humbler, less triumphant than some of its English or American counterparts. At its best, it’s deeply local — less a brand, more a community. It has a gentleness, a refusal to be grandiose that engenders deep affection rather than awe.

Welsh Anglicanism also has a wonderful stubbornness. After all, it survived being proscribed by the Cromwellians, socially shunned by Nonconformist, reviled by Nationalists, politically disestablished by Liberals, stripped of much of its assets at the same time, before being culturally side-lined by secularism. It persists not because it offers prestige or social capital (at least not anymore)— but because it is part of the spiritual bedrock of this country.

A Spirituality of Place

There is a profound spirituality of place woven into Welsh Anglicanism — something the theologian and poet R.S. Thomas, himself a Welsh priest, captured in his poems. Thomas was famously austere, often cantankerous, but his vision of holiness is best suited for the stones of the fields, the slow ploughing of the land, the windswept loneliness of the hills. And it is precisely this sense of the sacred — rough-hewn, unvarnished — that one still encounters in the churches of rural Wales.

Worship here can often seem, to outside eyes, a little rough around the edges. Services may be stumbled through; worship booklets may be amateurish and damp. And yet there’s a kind of unvarnished honesty in it all — a sense that faith isn’t a performance; indeed, it can often be a matter of endurance, a daily, sometimes difficult offering of the heart.

In many churches, the 1984 Prayer Book still holds sway — a dignified, Cranmerian liturgy that, like its 1662 predecessor, seems suited to these old places. And when at a wedding or a funeral the space fills with the heartfelt singing of a congregation — or, better yet, a male voice choir — it feels less like a concert and more like a glimpse of heaven breaking through.

And in the crowded churchyards, where generations of families lie buried side by side, the past remains intimately close. These aren’t anonymous cemeteries, but family gatherings: ancestors laid to rest next to the church whose bells once rang for their christenings and vows. Among them lie a few so old they may have known Newton’s threadbare parson.

Why It Matters

In an era when much of Christianity can feel obsessed with relevance, with innovation, with big buildings and bigger screens, rural Anglicanism in Wales offers a powerful counter-testimony.

It says: you don’t need to be flashy to be faithful. You don’t need to have a thousand people to form a real spiritual community. You don’t need to impress in order to endure.

You need roots. You need patience. You need to let the stones tell their stories.

There’s is an understated wonder in this form of Anglicanism — a faith that has worn rags yet kept singing, that has never had much worldly power yet engendered a fierce loyalty to place and people. It teaches that true strength often lies in quiet perseverance, that the sacred is often found not in the splendid but in the small, the steadfast, even the poor.

When I sit in the pews of a humble Welsh church, hearing the rain tap against the ancient glass, I feel connected not just to history, but to something deeper: a faith that has learned to weather the centuries, not by chasing after greatness, but by abiding.

And when I glance again at Newton’s “wretched Welsh parson in rags,” I can’t help but smile. Perhaps he wasn’t so wretched after all. Perhaps he knew something about holiness that we, in our age of noise and spectacle, would do well to remember.

Beautiful! Thanks. I knew RS Thomas was coming as I read, and then there he was.

I am currently trying to memorise 'Lore'

Thank you Mark for this thoughtfully crafted piece. I can identify with what you say. Further afield from your part of Wales are the truly simple small churches of Pistyll and Mwnt both ‘thin’ liminal places overlooking the Irish Sea. Wonderful!