Public Space, Sacred Ground

We Need a Proper Debate About the Use of Our Sacred Spaces

‘I hear your concern, Pauline,’ I said as gently as I could, ‘but please remember that the nave has always been public space.’

She gave me the sort of look I normally associate with long-serving churchwardens and retired headmistresses rather than kindly old ladies. Our annual flea market was about to open, and I’d allowed it to spill out of the hall into the west end of the church. Pauline, arms folded, wasn’t impressed.

‘That’s a place of prayer,’ she said in her soft Carolina accent. ‘Not a place to sell things. Don’t you know Jesus chased the money-changers out of the temple?’

I now recall that exchange with fond exasperation. Many years later and an ocean away, I often wonder what Pauline would have made of the harvest suppers I organised in Brecon Cathedral or the café that now operates in my present church’s side aisles. I fear she’d be disappointed in her former vicar, and perhaps she’d be right.

Throughout my ministry I’ve believed that, ideally, churches should be set aside for prayer, worship, and the building up of Christ’s Body. But ideals don’t pay heating bills or build fellowship when there’s no hall for gatherings. With attendance down and costs up, churches have learnt to treat their naves as assets—places that can host concerts, fairs, yoga classes, or film nights, sometimes to build community, sometimes simply to raise funds.

Stretching the Sacred

Since the pandemic, however, cathedrals and churches have stretched the idea of the nave as public space to its limits. Professionally organised raves, silent discos, and murder-mystery dinners have become commonplace. These events, usually arranged by companies selling “exclusive heritage venues,” profit from our sacred spaces. We may dress this up with talk of “mission” and “engagement,” but the impulse owes more to the entertainment industry than to holiness.

Some enjoy the novelty of dancing under Gothic vaulting, but most people—churchgoers or not—feel some degree of unease. They may not call it sacrilege, but they sense something disordered: that what was meant to serve God and the community has begun to serve commerce. When an event grows from parish life—when neighbours dine, sing, or even dance together in the place they also pray—something holy is sustained. When the same space is hired out as a venue, holiness becomes an aesthetic, not a reality.

Still, not all who defend such uses are cynical. Many sincerely believe the Church must inhabit the culture it hopes to serve. As Christ ate with outsiders, they say, so should we open our doors to art, joy, and experiment. If people won’t come for Evensong, perhaps they’ll come to dance—and discover that holiness needn’t be humourless. Their intention is to make the Church visible and alive.

Shock as a Strategy

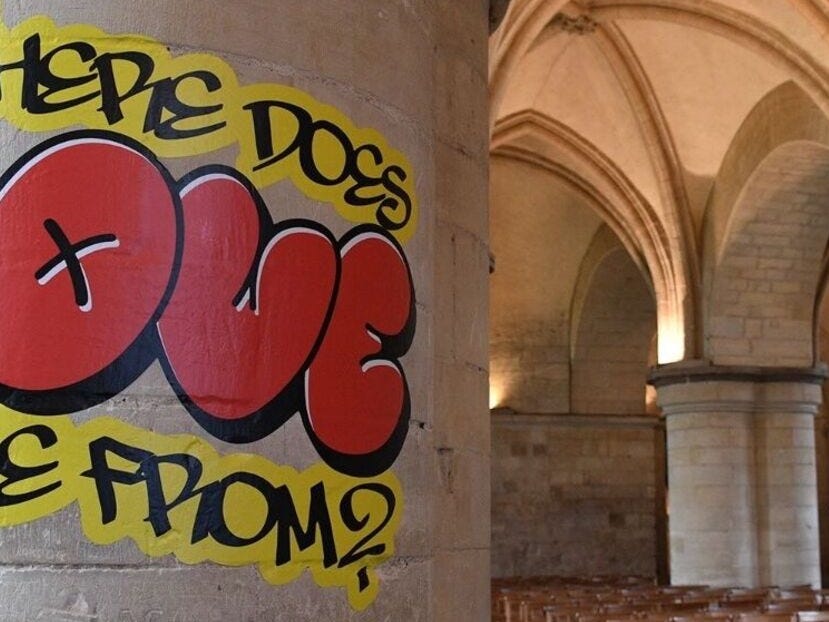

The uproar over the graffiti-style installation at Canterbury Cathedral follows similar logic. The exhibit covered parts of the ancient stonework with bright stickers bearing graffiti-like words and drawings. These grew from workshops with marginalised groups whose voices, it was said, were seldom heard within such venerable walls.

The organisers hoped to “create dialogue between the ancient and the contemporary.” The Dean and Chapter defended it as proof that spirituality evolves and the cathedral can converse with its time.

It was a thoughtful defence, and no doubt sincere. But they must have known the exhibit would offend—and likely counted on it. Shock has long been used as revelation. Indeed, it has become our shared reflex. What once belonged to the avant-garde has been taken up by the populist Right. The disdain for restraint that once defined the artistic rebel now animates political movements that delight in transgression for its own sake. Both treat offence as authenticity; outrage as a mark of righteousness. The same impulse that pastes stickers on medieval stone animates the jeers of leaders who mock civility. Each believes that to scandalise is to enlighten.

Yet reverence isn’t an obstacle to freedom. It’s what keeps freedom from curdling into contempt. A society that can’t bow before anything larger than itself will soon bow before nothing at all.

The Meaning of a Nave

Like my flea market long ago, these modern experiments rest on the argument that the nave has always been public space. That’s true enough. Many naves once hosted markets, courts, even festivities. Ordinary folk gathered there for news and trade. They were the crossroads of the sacred and civic.

But when we invoke that history to justify commercial events or transgressive displays, we misread it. The medieval market served neighbours, not promoters. It took place within a shared moral order where prayer and play were kin. Those gatherings emerged from within the parish itself: a community using its own space to sustain its common life. What happens now, too often, is the opposite—events imported from outside, designed for spectacle or profit, using the church as backdrop rather than honouring it as sacred space.

The question isn’t whether the nave can host human joy (it always could) but whether what we do there reflects courtesy, reverence, and genuine belonging rather than commerce and corporate branding.

This, perhaps, is what troubles me most about Canterbury’s graffiti. For all its talk of inclusion, it feels like a gesture performed for the marginalised, not with them—a symbolic act of solidarity carried out by those already in authority. It’s easier to paste bright slogans on stone than to welcome those same voices into the worshipping community: to give them not a sticker on a wall but a seat at the table. Symbolism can be powerful, but it can also replace compassion that costs something. Would the Dean and Chapter have permitted an exhibit that challenged their own sensibilities? Too often, gestures of inclusion become spectacles of self-congratulation.

Still, we mustn’t let frustration with hollow gestures harden into suspicion of creativity. A living building must breathe the air of its community. Concerts, lectures, playgroups, and suppers can all honour local life. I’ve no wish to divide “high” from “low” culture; dignity and vulgarity come from the heart, not the genre. The issue is posture, not performance. Is the event conducted with care for its context? Does it build neighbourliness or merely sell an experience?

A nave, even when used for ordinary things, remains consecrated space. It holds the memory of joys and griefs, of persons whose dignity was recognised before God. To step inside, whether in faith or doubt, is to enter a continuity of love. Courtesy is the right response—not stiffness, but attentiveness, the willingness to listen before speaking.

Toward an Edifying Use

Even defenders of discos and graffiti admit that reverence is fragile. Their hope is that joy, play, and artistic risk can coexist with holiness—that widening the Church’s welcome keeps its doors open for grace. They’re right to want that. But good intentions don’t erase consequences. Reverence, once frayed, is hard to mend.

A professionally organised disco beneath stained glass may fill coffers and stir curiosity, but it also teaches a different lesson: that nothing is too sacred to be exploited. By contrast, a concert arranged by parishioners, a harvest supper, or a local fair builds friendship and gratitude—life shared, not experience sold. The difference lies not in the activity but in the spirit that animates it.

Our culture prizes novelty; churches feel pressure to compete. Yet the Church’s gift isn’t entertainment—it’s depth. Reverence and courtesy aren’t enemies of freedom; they are its tutors. If we can’t find stillness here, where will we find it?

The architecture itself insists on that truth. The nave’s long perspective draws the eye forward and upward, suggesting pilgrimage. To fill it with spectacle flattens that invitation into showmanship. We needn’t guard our buildings with puritan gloom, but we must let them remain holy—set apart so that anyone who enters may sense that love of God and neighbour gives meaning to the space.

And so, if churches are to host art that makes people think, it should be art that listens before it speaks—art that arises from dialogue with the community and honours the place rather than exploiting it. Anything that treats the church as a stage or brand mistakes attention for meaning. True art in such a setting will edify more than shock: it will invite visitors toward gratitude, understanding, and neighbourliness—and leave space, always, for the holy hush that stillness makes.

Edification and the Common Good

None of this is an argument for gloom. A church worth belonging to should contain laughter, music, the smell of good food, and even thought-provoking art exhibits. Markets and suppers have their place when they grow from the life of the community that surrounds and inhabits them. These things serve best when animated by the same spirit that ought to animate worship: gratitude, fairness, humility.

The old word for that is edification—strengthening what might otherwise crumble. A market that lets neighbours meet, a concert that draws us toward beauty, a talk that deepens understanding—all build communion rather than feed consumption. Commercialisation, by contrast, is a kind of acid. It eats at whatever it touches, turning meaning into marketing. Once a nave is treated as just another commercial space, its soul begins to leak away.

Perhaps this isn’t a matter for rules. What we need isn’t more policy but deeper discernment. The question is less what we do than how and why—and who is invited into that conversation. We need clergy and congregations, artists and neighbours, worshippers and wanderers to listen together about what it means to inhabit the sacred in common life—and to welcome that life into our sacred spaces in ways that honour both. For the nave has always belonged to God, and through him to his people. Its meaning isn’t something we invent, but something we receive—a gift entrusted to our care.

The graffiti on cathedral stone was undoubtedly meant to begin such a conversation, but perhaps it spoke too quickly—more performance than prayer. If we’re to learn from it, let it be by finding ways to hear those unheard voices not through spectacle, but through an enduring life together.

The true dialogue between the ancient and the contemporary won’t be plastered on the walls but lived out in fellowship within them.

This is excellent, thank you - I'm going to share it with my PCC!

Our local cathedral hosts silent discos from time to time. I have never been but some work colleagues have and what struck me was how they talked afterwards about feeling like the cathedral was a space for all and how nice it was to feel that. I don't think any started to attend services or anything but is that our only measure of 'success'? It's a sacred space they feel is accessible if/when they need one.